Night Bazaars

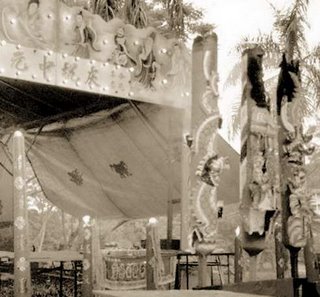

Pasar malam or night bazaar in Malay is the mall of yester years. Two blocks away from Block 13 was a large canal with a wide footpath, the normal quiet walkway came alive during the weekends with the night bazaar. Peddlers with make shift stores displayed a wide range of goods and services lined up the walkway lit with kerosene lamps making it a hive of activities as residents swarmed to enjoy the revelry.

We could not, as usual, afford a lot of things and would resort to pilfering by coming up with a strategy to avoid been caught. Our brilliant idea was inspired by the fact that these stalls were badly lit by kerosene lamps. The vendors would therefore not be able to notice much if we approached him in a big group. We would then haggle for cheaper prices, and while the vendor lapsed into a moment of inattention, one of us would move in and pinched whatever we fancied.

Durian was our favourite as it was expensive back then and considered an indelegnce. The Malays had a saying “pawn the sarong for the durian”. Durians were usually displayed on the ground and we would crowd round the made shift store and Richard with his matured look would pretend to haggle for cheaper prices to distract the seller. Conveniently, one of us would kick the durian backwards where someone was waiting to pick it up and walked away.

Over the durians we would often boast and outbid each other of our daring exploits to the point of cooking up tales in order not to be outdone.

Proven techniques used on the mama store were repeated to our delight. Fitness counted and you got no one to blame if you are caught.